OSCC USA Causal-Mechanical Edifice

OSCC USA Causal-Mechanical Edifice

Cause and result have a direct relationship where the cause is always positioned before the result, and the result is

always equal to and proportional to the cause—in the normal flow of time to normal chronological events.

Special flow of time may include non-chronology in that a cause which is at a circumstantial position after the result

may yet then reposition the result in the normal flow of time to chronological events.

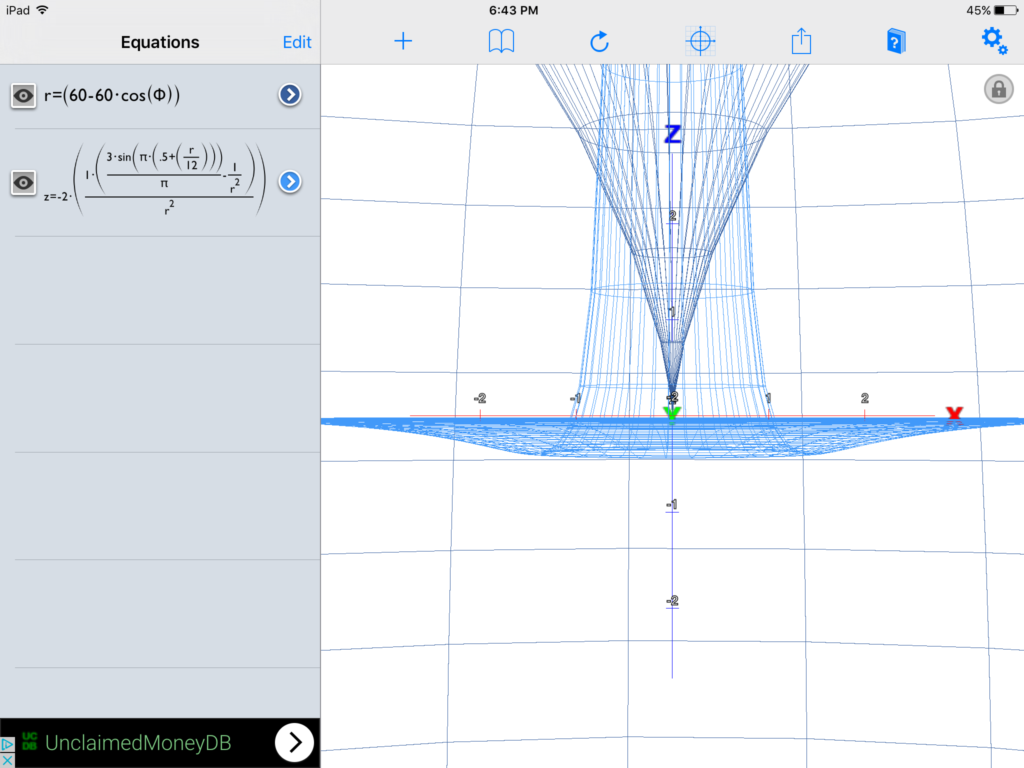

Identification of the critical difference within the flow of time separating a unified singular cause different yet equal

from a unified singular result is necessary through the empty dimensionless latticework separating material.

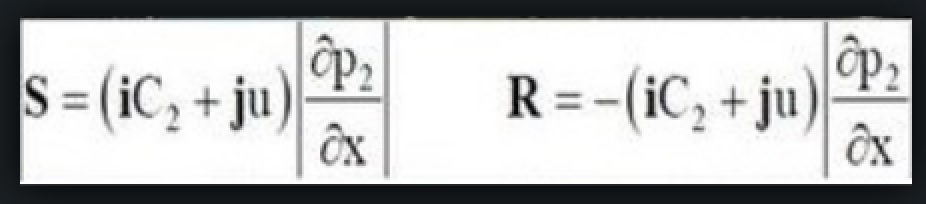

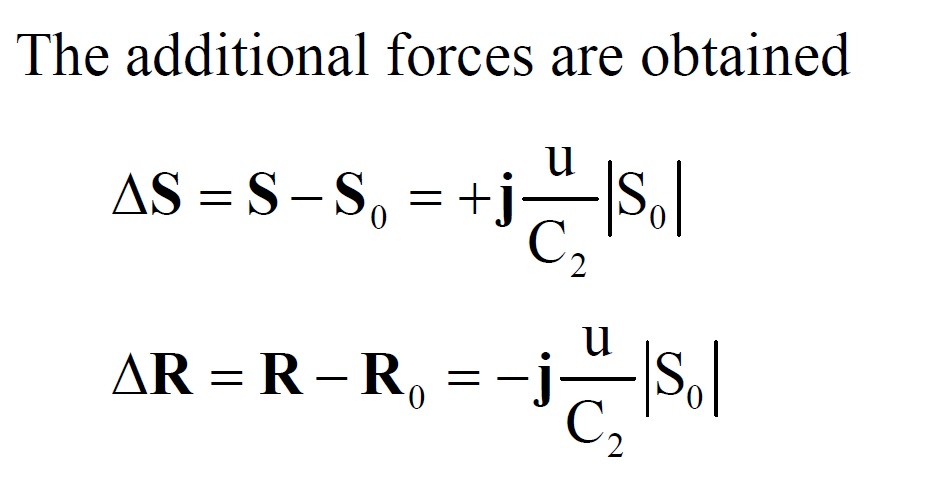

The causal-mechanical equation allows Open Source Civilian Control of The United States of America’s Principal

Officer to create an increase of the fixed positive signature for the asymmetric flow within time from how a cause and

result are inertially positioned for use with Constitutional Oaths.

This is how an inertial impact identity retains its protection to and from the plural possessive value of Constitutional

jurisprudence to prove a universal directivity or pattern, locally.

The OSCC USA Causal-Mechanical Edifice — 3 Axioms and Equation:

First Axiom:

Time possesses a quality, creating a difference in causes and results. This is detectable with directivity or pattern. This

property determines the difference of the present; and, either, or past and future. Proceeding from those circumstances

in which: 1) The cause exalts the result outside of the body in which the result is realized and 2) the result sets in after

the cause.

Second Axiom:

Causes and results are always separated by space. Therefore, between them exists an arbitrarily small, but not equaling zero, spatial difference.

Third Axiom:

Causes and results are separated in time. Therefore, between their appearance there exists an arbitrarily small, but not equaling zero time difference of a fixed sign.

Common Definition of time

NOUN

– the indefinite continued progress of existence and events in the past, present, and future regarded as a whole.

– a point of time as measured in hours and minutes past midnight or noon.

VERB

– plan, schedule, or arrange when (something) should happen or be done.

Simple Definition of time

: the thing that is measured as seconds, minutes, hours, days, years, etc.

: a particular minute or hour shown by a clock

: the time in a particular area or part of the world

Full Definition for Time:

1 a : the measured or measurable period during which an action, process, or condition exists or continues : durationb : a nonspatial continuum that is measured in terms of events which succeed one another from past through present to futurec : leisure

2 : the point or period when something occurs : occasion

3 a : an appointed, fixed, or customary moment or hour for something to happen, begin, or end b : an opportune or suitable moment —often used in the phrase about time

4 a : a historical period : ageb : a division of geologic chronologyc : conditions at present or at some specified period —usually used in plural d : the present time

5 a : lifetimeb : a period of apprenticeshipc : a term of military serviced : a prison sentence

6 : season

7 a : rate of speed : tempob : the grouping of the beats of music : rhythm

8 a : a moment, hour, day, or year as indicated by a clock or calendar b : any of various systems (as sidereal or solar) of reckoning time

9 a : one of a series of recurring instances or repeated actions <you’ve been told many times>b plural (1) : added or accumulated quantities or instances (2) : equal fractional parts of which an indicated number equal a comparatively greater quantity

c : turn

10 : finite as contrasted with infinite duration

11 : a person’s experience during a specified period or on a particular occasion

12 a : the hours or days required to be occupied by one’s work b : an hourly pay rate c : wages paid at discharge or resignation

13 a : the playing time of a gameb : time-out 1

14 : a period during which something is used or available for use

Phrases for Time

at the same time

: nevertheless, yet

at times

: at intervals : occasionally

for the time being

: for the present

from time to time

: once in a while : occasionally

in no time

: very quickly or soon

in time

1 : sufficiently early

2 : eventually

3 : in correct tempo

on time

1 a : at the appointed timeb : on schedule

2 : on the installment plan

time and again

: frequently, repeatedly

Legal References for Time

Full Definitions of Time in Law

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

Rule 6. Computing and Extending Time; Time for Motion Papers

(a) Computing Time. The following rules apply in computing any time period specified in these rules, in any local rule or court order, or in any statute that does not specify a method of computing time.

(1) Period Stated in Days or a Longer Unit. When the period is stated in days or a longer unit of time:

(A) exclude the day of the event that triggers the period;

(B) count every day, including intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays; and

(C) include the last day of the period, but if the last day is a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday, the period continues to run until the end of the next day that is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday.

(2) Period Stated in Hours. When the period is stated in hours:

(A) begin counting immediately on the occurrence of the event that triggers the period;

(B) count every hour, including hours during intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays; and

(C) if the period would end on a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday, the period continues to run until the same time on the next day that is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday.

(3) Inaccessibility of the Clerk’s Office. Unless the court orders otherwise, if the clerk’s office is inaccessible:

(A) on the last day for filing under Rule 6(a)(1), then the time for filing is extended to the first accessible day that is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday; or

(B) during the last hour for filing under Rule 6(a)(2), then the time for filing is extended to the same time on the first accessible day that is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday.

(4) “Last Day” Defined. Unless a different time is set by a statute, local rule, or court order, the last day ends:

(A) for electronic filing, at midnight in the court’s time zone; and

(B) for filing by other means, when the clerk’s office is scheduled to close.

(5) “Next Day” Defined. The “next day” is determined by continuing to count forward when the period is measured after an event and backward when measured before an event.

(6) “Legal Holiday” Defined. “Legal holiday” means:

(A) the day set aside by statute for observing New Year’s Day, Martin Luther King Jr.’s Birthday, Washington’s Birthday, Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Columbus Day, Veterans’ Day, Thanksgiving Day, or Christmas Day;

(B) any day declared a holiday by the President or Congress; and

(C) for periods that are measured after an event, any other day declared a holiday by the state where the district court is located.

(b) Extending Time.

(1) In General. When an act may or must be done within a specified time, the court may, for good cause, extend the time:

(A) with or without motion or notice if the court acts, or if a request is made, before the original time or its extension expires; or

(B) on motion made after the time has expired if the party failed to act because of excusable neglect.

(2) Exceptions. A court must not extend the time to act under Rules 50(b) and (d), 52(b), 59(b), (d), and (e), and 60(b).

(c) Motions, Notices of Hearing, and Affidavits.

(1) In General. A written motion and notice of the hearing must be served at least 14 days before the time specified for the hearing, with the following exceptions:

(A) when the motion may be heard ex parte;

(B) when these rules set a different time; or

(C) when a court order—which a party may, for good cause, apply for ex parte—sets a different time.

(2) Supporting Affidavit. Any affidavit supporting a motion must be served with the motion. Except as Rule 59(c) provides otherwise, any opposing affidavit must be served at least 7 days before the hearing, unless the court permits service at another time.

(d) Additional Time After Certain Kinds of Service. When a party may or must act within a specified time after being served and service is made under Rule 5(b)(2)(C) (mail), (D)(leaving with the clerk), or (F) (other means consented to), 3 days are added after the period would otherwise expire under Rule 6(a).

Notes

(As amended Dec. 27, 1946, eff. Mar. 19, 1948; Jan. 21, 1963, eff. July 1, 1963; Feb. 28, 1966, eff. July 1, 1966; Dec. 4, 1967, eff. July 1, 1968; Mar. 1, 1971, eff. July 1, 1971; Apr. 28, 1983, eff. Aug. 1, 1983; Apr. 29, 1985, eff. Aug. 1, 1985; Mar. 2, 1987, eff. Aug. 1, 1987; Apr. 26, 1999, eff. Dec. 1, 1999; Apr. 23, 2001, eff. Dec. 1, 2001; Apr. 25, 2005, eff. Dec. 1, 2005; Apr. 30, 2007, eff. Dec. 1, 2007; Mar. 26, 2009, eff. Dec. 1, 2009; Apr. 28, 2016, eff. Dec 1, 2016.)

Notes of Advisory Committee on Rules—1937

Note to Subdivisions (a) and (b). These are amplifications along lines common in state practices, of [former] Equity Rule 80 (Computation of Time—Sundays and Holidays) and of the provisions for enlargement of time found in [former] Equity Rules 8 (Enforcement of Final Decrees) and 16 (Defendant to Answer—Default—Decree Pro Confesso). See also Rule XIII, Rules and Forms in Criminal Cases, 292 U.S. 661, 666 (1934). Compare Ala.Code Ann. (Michie, 1928) §13 and former Law Rule 8 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia (1924), superseded in 1929 by Law Rule 8, Rules of the District Court of the United States for the District of Columbia (1937).

Note to Subdivision (c). This eliminates the difficulties caused by the expiration of terms of court. Such statutes as U.S.C. Title 28, [former] §12 (Trials not discontinued by new term) are not affected. Compare Rules of the United States District Court of Minnesota, Rule 25 (Minn.Stat. (Mason, Supp. 1936), p. 1089).

Note to Subdivision (d). Compare 2 Minn.Stat. (Mason, 1927) §9246; N.Y.R.C.P. (1937) Rules 60 and 64.

Notes of Advisory Committee on Rules—1946 Amendment

Subdivision (b). The purpose of the amendment is to clarify the finality of judgments. Prior to the advent of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the general rule that a court loses jurisdiction to disturb its judgments, upon the expiration of the term at which they were entered, had long been the classic device which (together with the statutory limits on the time for appeal) gave finality to judgments. See Note to Rule 73(a). Rule 6(c) abrogates that limit on judicial power. That limit was open to many objections, one of them being inequality of operation because, under it, the time for vacating a judgment rendered early in a term was much longer than for a judgment rendered near the end of the term.

The question to be met under Rule 6(b) is: how far should the desire to allow correction of judgments be allowed to postpone their finality? The rules contain a number of provisions permitting the vacation or modification of judgments on various grounds. Each of these rules contains express time limits on the motions for granting of relief. Rule 6(b) is a rule of general application giving wide discretion to the court to enlarge these time limits or revive them after they have expired, the only exceptions stated in the original rule being a prohibition against enlarging the time specified in Rule 59(b) and (d) for making motions for or granting new trials, and a prohibition against enlarging the time fixed by law for taking an appeal. It should also be noted that Rule 6(b) itself contains no limitation of time within which the court may exercise its discretion, and since the expiration of the term does not end its power, there is now no time limit on the exercise of its discretion under Rule 6(b).

Decisions of lower federal courts suggest that some of the rules containing time limits which may be set aside under Rule 6(b) are Rules 25, 50(b), 52(b), 60(b), and 73(g).

In a number of cases the effect of Rule 6(b) on the time limitations of these rules has been considered. Certainly the rule is susceptible of the interpretation that the court is given the power in its discretion to relieve a party from failure to act within the times specified in any of these other rules, with only the exceptions stated in Rule 6(b), and in some cases the rule has been so construed.

With regard to Rule 25(a) for substitution, it was held in Anderson v. Brady (E.D.Ky. 1941) 4 Fed.Rules Service 25a.1, Case 1, and in Anderson v. Yungkau (C.C.A. 6th, 1946) 153 F.(2d) 685, cert. granted (1946) 66 S.Ct. 1025, that under Rule 6(b) the court had no authority to allow substitution of parties after the expiration of the limit fixed in Rule 25(a).

As to Rules 50(b) for judgments notwithstanding the verdict and 52(b) for amendment of findings and vacation of judgment, it was recognized in Leishman v. Associated Wholesale Electric Co. (1943) 318 U.S. 203, that Rule 6(b) allowed the district court to enlarge the time to make a motion for amended findings and judgment beyond the limit expressly fixed in Rule 52(b). See Coca-Cola v. Busch (E.D.Pa. 1943) 7 Fed.Rules Service 59b.2, Case 4. Obviously, if the time limit in Rule 52(b) could be set aside under Rule 6(b), the time limit in Rule 50(b) for granting judgment notwithstanding the verdict (and thus vacating the judgment entered “forthwith” on the verdict) likewise could be set aside.

As to Rule 59 on motions for a new trial, it has been settled that the time limits in Rule 59(b) and (d) for making motions for or granting new trial could not be set aside under Rule 6(b), because Rule 6(b) expressly refers to Rule 59, and forbids it. See Safeway Stores, Inc. v. Coe (App.D.C. 1943) 136 F.(2d) 771; Jusino v. Morales & Tio (C.C.A. 1st, 1944) 139 F.(2d) 946; Coca-Cola Co. v. Busch (E.D.Pa. 1943) 7 Fed.Rules Service 59b.2, Case 4; Peterson v. Chicago Great Western Ry. Co. (D.Neb. 1943) 7 Fed.Rules Service 59b.2, Case 1; Leishman v. Associated Wholesale Electric Co. (1943) 318 U.S. 203.

As to Rule 60(b) for relief from a judgment, it was held in Schram v. O’Connor (E.D.Mich. 1941) 5 Fed.Rules Serv. 6b.31, Case 1, 2 F.R.D. 192, s. c. 5 Fed.Rules Serv. 6b.31, Case 2, F.R.D. 192, that the six-months time limit in original Rule 60(b) for making a motion for relief from a judgment for surprise, mistake, or excusable neglect could be set aside under Rule 6(b). The contrary result was reached in Wallace v. United States (C.C.A.2d, 1944) 142 F.(2d) 240, cert. den. (1944) 323 U.S. 712; Reed v. South Atlantic Steamship Co. of Del. (D.Del. 1942) 6 Fed.Rules Serv. 60b.31, Case 1.

As to Rule 73(g), fixing the time for docketing an appeal, it was held in Ainsworth v. Gill Glass & Fixture Co. (C.C.A.3d, 1939) 104 F.(2d) 83, that under Rule 6(b) the district court, upon motion made after the expiration of the forty-day period, stated in Rule 73(g), but before the expiration of the ninety-day period therein specified, could permit the docketing of the appeal on a showing of excusable neglect. The contrary was held in Mutual Benefit Health & Accident Ass’n v. Snyder (C.C.A. 6th, 1940) 109 F.(2d) 469 and in Burke v. Canfield(App.D.C. 1940) 111 F.(2d) 526.

The amendment of Rule 6(b) now proposed is based on the view that there should be a definite point where it can be said a judgment is final; that the right method of dealing with the problem is to list in Rule 6(b) the various other rules whose time limits may not be set aside, and then, if the time limit in any of those other rules is too short, to amend that other rule to give a longer time. The further argument is that Rule 6(c) abolished the long standing device to produce finality in judgments through expiration of the term, and since that limitation on the jurisdiction of courts to set aside their own judgments has been removed by Rule 6(c), some other limitation must be substituted or judgments never can be said to be final.

In this connection reference is made to the established rule that if a motion for new trial is seasonably made, the mere making or pendency of the motion destroys the finality of the judgment, and even though the motion is ultimately denied, the full time for appeal starts anew from the date of denial. Also, a motion to amend the findings under Rule 52(b) has the same effect on the time for appeal. Leishman v. Associated Wholesale Electric Co. (1943) 318 U.S. 203. By the same reasoning a motion for judgment under Rule 50(b), involving as it does the vacation of a judgment entered “forthwith” on the verdict (Rule 58), operates to postpone, until an order is made, the running of the time for appeal. The Committee believes that the abolition by Rule 6(c) of the old rule that a court’s power over its judgments ends with the term, requires a substitute limitation, and that unless Rule 6(b) is amended to prevent enlargement of the times specified in Rules 50(b), 52(b) and 60(b), and the limitation as to Rule 59(b) and (d) is retained, no one can say when a judgment is final. This is also true with regard to proposed Rule 59(e), which authorizes a motion to alter or amend a judgment, hence that rule is also included in the enumeration in amended Rule 6(b). In consideration of the amendment, however, it should be noted that Rule 60(b) is also to be amended so as to lengthen the six-months period originally prescribed in that rule to one year.

As to Rule 25 on substitution, while finality is not involved, the limit there fixed should be controlling. That rule, as amended, gives the court power, upon showing of a reasonable excuse, to permit substitution after the expiration of the two-year period.

As to Rule 73(g), it is believed that the conflict in decisions should be resolved and not left to further litigation, and that the rule should be listed as one whose limitation may not be set aside under Rule 6(b).

As to Rule 59(c), fixing the time for serving affidavits on motion for new trial, it is believed that the court should have authority under Rule 6(b) to enlarge the time, because, once the motion for new trial is made, the judgment no longer has finality, and the extension of time for affidavits thus does not of itself disturb finality.

Other changes proposed in Rule 6(b) are merely clarifying and conforming. Thus “request” is substituted for “application” in clause (1) because an application is defined as a motion under Rule 7(b). The phrase “extend the time” is substituted for “enlarge the period” because the former is a more suitable expression and relates more clearly to both clauses (1) and (2). The final phrase in Rule 6(b), “or the period for taking an appeal as provided by law”, is deleted and a reference to Rule 73(a) inserted, since it is proposed to state in that rule the time for appeal to a circuit court of appeals, which is the only appeal governed by the Federal Rules, and allows an extension of time. See Rule 72.

Subdivision (c). The purpose of this amendment is to prevent reliance upon the continued existence of a term as a source of power to disturb the finality of a judgment upon grounds other than those stated in these rules. See Hill v. Hawes (1944) 320 U.S. 520; Boaz v. Mutual Life Ins. Co. of New York (C.C.A. 8th, 1944) 146 F.(2d) 321; Bucy v. Nevada Construction Co. (C.C.A. 9th, 1942) 125 F.(2d) 213.

Notes of Advisory Committee on Rules—1963 Amendment

Subdivision (a). This amendment is related to the amendment of Rule 77(c) changing the regulation of the days on which the clerk’s office shall be open.

The wording of the first sentence of Rule 6(a) is clarified and the subdivision is made expressly applicable to computing periods of time set forth in local rules.

Saturday is to be treated in the same way as Sunday or a “legal holiday” in that it is not to be included when it falls on the last day of a computed period, nor counted as an intermediate day when the period is less than 7 days. “Legal holiday” is defined for purposes of this subdivision and amended Rule 77(c). Compare the definition of “holiday” in 11 U.S.C. §1 (18); also 5 U.S.C. §86a; Executive Order No. 10358, “Observance of Holidays,” June 9, 1952, 17 Fed.Reg. 5269. In the light of these changes the last sentence of the present subdivision, dealing with half holidays, is eliminated.

With Saturdays and State holidays made “dies non” in certain cases by the amended subdivision, computation of the usual 5–day notice of motion or the 2–day notice to dissolve or modify a temporary restraining order may work out so as to cause embarrassing delay in urgent cases. The delay can be obviated by applying to the court to shorten the time, see Rules 6(d) and 65(b).

Subdivision (b). The prohibition against extending the time for taking action under Rule 25 (Substitution of parties) is eliminated. The only limitation of time provided for in amended Rule 25 is the 90–day period following a suggestion upon the record of the death of a party within which to make a motion to substitute the proper parties for the deceased party. See Rule 25(a)(1), as amended, and the Advisory Committee’s Note thereto. It is intended that the court shall have discretion to enlarge that period.

Notes of Advisory Committee on Rules—1968 Amendment

The amendment eliminates the references to Rule 73, which is to be abrogated.

P. L. 88–139, §1, 77 Stat. 248, approved on October 16, 1963, amended 28 U.S.C. §138 to read as follows: “The district court shall not hold formal terms.” Thus Rule 6(c) is rendered unnecessary, and it is rescinded.

Notes of Advisory Committee on Rules—1971 Amendment

The amendment adds Columbus Day to the list of legal holidays to conform the subdivision to the Act of June 28, 1968, 82 Stat. 250, which constituted Columbus Day a legal holiday effective after January 1, 1971.

The Act, which amended Title 5, U.S.C., §6103(a), changes the day on which certain holidays are to be observed. Washington’s Birthday, Memorial Day and Veterans Day are to be observed on the third Monday in February, the last Monday in May and the fourth Monday in October, respectively, rather than, as heretofore, on February 22, May 30, and November 11, respectively. Columbus Day is to be observed on the second Monday in October. New Year’s Day, Independence Day, Thanksgiving Day and Christmas continue to be observed on the traditional days.

Notes of Advisory Committee on Rules—1983 Amendment

Subdivision (b). The amendment confers finality upon the judgments of magistrates by foreclosing enlargement of the time for appeal except as provided in new Rule 74(a) (20 day period for demonstration of excusable neglect).

Notes of Advisory Committee on Rules—1985 Amendment

Rule 6(a) is amended to acknowledge that weather conditions or other events may render the clerk’s office inaccessible one or more days. Parties who are obliged to file something with the court during that period should not be penalized if they cannot do so. The amendment conforms to changes made in Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 45 (a), effective August 1, 1982.

The Rule also is amended to extend the exclusion of intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays to the computation of time periods less than 11 days. Under the current version of the Rule, parties bringing motions under rules with 10-day periods could have as few as 5 working days to prepare their motions. This hardship would be especially acute in the case of Rules 50(b) and (c)(2), 52(b), and 59(b), (d), and (e), which may not be enlarged at the discretion of the court. See Rule 6(b). If the exclusion of Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays will operate to cause excessive delay in urgent cases, the delay can be obviated by applying to the court to shorten the time, See Rule 6(b).

The Birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr., which becomes a legal holiday effective in 1986, has been added to the list of legal holidays enumerated in the Rule.

Notes of Advisory Committee on Rules—1987 Amendment

The amendments are technical. No substantive change is intended.

Committee Notes on Rules—1999 Amendment

The reference to Rule 74(a) is stricken from the catalogue of time periods that cannot be extended by the district court. The change reflects the 1997 abrogation of Rule 74(a).

Committee Notes on Rules—2001 Amendment

The additional three days provided by Rule 6(e) is extended to the means of service authorized by the new paragraph (D) added to Rule 5(b), including—with the consent of the person served—service by electronic or other means. The three-day addition is provided as well for service on a person with no known address by leaving a copy with the clerk of the court.

Changes Made After Publication and Comments. Proposed Rule 6(e) is the same as the “alternative proposal” that was published in August 1999.

Committee Notes on Rules—2005 Amendment

Rule 6(e) is amended to remove any doubt as to the method for extending the time to respond after service by mail, leaving with the clerk of court, electronic means, or other means consented to by the party served. Three days are added after the prescribed period otherwise expires under Rule 6(a). Intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays are included in counting these added three days. If the third day is a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday, the last day to act is the next day that is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday. The effect of invoking the day when the prescribed period would otherwise expire under Rule 6(a) can be illustrated by assuming that the thirtieth day of a thirty-day period is a Saturday. Under Rule 6(a) the period expires on the next day that is not a Sunday or legal holiday. If the following Monday is a legal holiday, under Rule 6(a) the period expires on Tuesday. Three days are then added—Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday as the third and final day to act. If the period prescribed expires on a Friday, the three added days are Saturday, Sunday, and Monday, which is the third and final day to act unless it is a legal holiday. If Monday is a legal holiday, the next day that is not a legal holiday is the third and final day to act.

Application of Rule 6(e) to a period that is less than eleven days can be illustrated by a paper that is served by mailing on a Friday. If ten days are allowed to respond, intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays are excluded in determining when the period expires under Rule 6(a). If there is no legal holiday, the period expires on the Friday two weeks after the paper was mailed. The three added Rule 6(e) days are Saturday, Sunday, and Monday, which is the third and final day to act unless it is a legal holiday. If Monday is a legal holiday, the next day that is not a legal holiday is the final day to act.

Changes Made After Publication and Comment. Changes were made to clarify further the method of counting the three days added after service under Rule 5(b)(2)(B), (C), or (D).

Committee Notes on Rules—2007 Amendment

The language of Rule 6 has been amended as part of the general restyling of the Civil Rules to make them more easily understood and to make style and terminology consistent throughout the rules. These changes are intended to be stylistic only.

Committee Notes on Rules—2009 Amendment

Subdivision (a). Subdivision (a) has been amended to simplify and clarify the provisions that describe how deadlines are computed. Subdivision (a) governs the computation of any time period found in these rules, in any local rule or court order, or in any statute that does not specify a method of computing time. In accordance with Rule 83(a)(1), a local rule may not direct that a deadline be computed in a manner inconsistent with subdivision (a).

The time-computation provisions of subdivision (a) apply only when a time period must be computed. They do not apply when a fixed time to act is set. The amendments thus carry forward the approach taken in Violette v. P.A. Days, Inc., 427 F.3d 1015, 1016 (6th Cir. 2005) (holding that Civil Rule 6(a) “does not apply to situations where the court has established a specific calendar day as a deadline”), and reject the contrary holding of In re American Healthcare Management, Inc., 900 F.2d 827, 832 (5th Cir. 1990) (holding that Bankruptcy Rule 9006(a) governs treatment of date-certain deadline set by court order). If, for example, the date for filing is “no later than November 1, 2007,” subdivision (a) does not govern. But if a filing is required to be made “within 10 days” or “within 72 hours,” subdivision (a) describes how that deadline is computed.

Subdivision (a) does not apply when computing a time period set by a statute if the statute specifies a method of computing time. See, e.g., 2 U.S.C. §394 (specifying method for computing time periods prescribed by certain statutory provisions relating to contested elections to the House of Representatives).

Subdivision (a)(1). New subdivision (a)(1) addresses the computation of time periods that are stated in days. It also applies to time periods that are stated in weeks, months, or years. See, e.g., Rule 60(c)(1). Subdivision (a)(1)(B)’s directive to “count every day” is relevant only if the period is stated in days (not weeks, months or years).

Under former Rule 6(a), a period of 11 days or more was computed differently than a period of less than 11 days. Intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays were included in computing the longer periods, but excluded in computing the shorter periods. Former Rule 6(a) thus made computing deadlines unnecessarily complicated and led to counterintuitive results. For example, a 10-day period and a 14-day period that started on the same day usually ended on the same day—and the 10-day period not infrequently ended later than the 14-day period. See Miltimore Sales, Inc. v. Int’l Rectifier, Inc., 412 F.3d 685, 686 (6th Cir. 2005).

Under new subdivision (a)(1), all deadlines stated in days (no matter the length) are computed in the same way. The day of the event that triggers the deadline is not counted. All other days—including intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays—are counted, with only one exception: If the period ends on a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday, then the deadline falls on the next day that is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday. An illustration is provided below in the discussion of subdivision (a)(5). Subdivision (a)(3) addresses filing deadlines that expire on a day when the clerk’s office is inaccessible.

Where subdivision (a) formerly referred to the “act, event, or default” that triggers the deadline, new subdivision (a) refers simply to the “event” that triggers the deadline; this change in terminology is adopted for brevity and simplicity, and is not intended to change meaning.

Periods previously expressed as less than 11 days will be shortened as a practical matter by the decision to count intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays in computing all periods. Many of those periods have been lengthened to compensate for the change. See, e.g., Rule 14(a)(1).

Most of the 10-day periods were adjusted to meet the change in computation method by setting 14 days as the new period. A 14-day period corresponds to the most frequent result of a 10-day period under the former computation method—two Saturdays and two Sundays were excluded, giving 14 days in all. A 14-day period has an additional advantage. The final day falls on the same day of the week as the event that triggered the period—the 14th day after a Monday, for example, is a Monday. This advantage of using week-long periods led to adopting 7-day periods to replace some of the periods set at less than 10 days, and 21-day periods to replace 20-day periods. Thirty-day and longer periods, however, were generally retained without change.

Subdivision (a)(2). New subdivision (a)(2) addresses the computation of time periods that are stated in hours. No such deadline currently appears in the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. But some statutes contain deadlines stated in hours, as do some court orders issued in expedited proceedings.

Under subdivision (a)(2), a deadline stated in hours starts to run immediately on the occurrence of the event that triggers the deadline. The deadline generally ends when the time expires. If, however, the time period expires at a specific time (say, 2:17 p.m.) on a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday, then the deadline is extended to the same time (2:17 p.m.) on the next day that is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday. Periods stated in hours are not to be “rounded up” to the next whole hour. Subdivision (a)(3) addresses situations when the clerk’s office is inaccessible during the last hour before a filing deadline expires.

Subdivision (a)(2)(B) directs that every hour be counted. Thus, for example, a 72-hour period that commences at 10:23 a.m. on Friday, November 2, 2007, will run until 9:23 a.m. on Monday, November 5; the discrepancy in start and end times in this example results from the intervening shift from daylight saving time to standard time.

Subdivision (a)(3). When determining the last day of a filing period stated in days or a longer unit of time, a day on which the clerk’s office is not accessible because of the weather or another reason is treated like a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday. When determining the end of a filing period stated in hours, if the clerk’s office is inaccessible during the last hour of the filing period computed under subdivision (a)(2) then the period is extended to the same time on the next day that is not a weekend, holiday, or day when the clerk’s office is inaccessible.

Subdivision (a)(3)’s extensions apply “[u]nless the court orders otherwise.” In some circumstances, the court might not wish a period of inaccessibility to trigger a full 24-hour extension; in those instances, the court can specify a briefer extension.

The text of the rule no longer refers to “weather or other conditions” as the reason for the inaccessibility of the clerk’s office. The reference to “weather” was deleted from the text to underscore that inaccessibility can occur for reasons unrelated to weather, such as an outage of the electronic filing system. Weather can still be a reason for inaccessibility of the clerk’s office. The rule does not attempt to define inaccessibility. Rather, the concept will continue to develop through caselaw, see, e.g., William G. Phelps, When Is Office of Clerk of Court Inaccessible Due to Weather or Other Conditions for Purpose of Computing Time Period for Filing Papers under Rule 6(a) of Federal Rules of Civil Procedure , 135 A.L.R. Fed. 259 (1996) (collecting cases). In addition, many local provisions address inaccessibility for purposes of electronic filing, see, e.g., D. Kan. Rule 5.4.11 (“A Filing User whose filing is made untimely as the result of a technical failure may seek appropriate relief from the court.”).

Subdivision (a)(4). New subdivision (a)(4) defines the end of the last day of a period for purposes of subdivision (a)(1). Subdivision (a)(4) does not apply in computing periods stated in hours under subdivision (a)(2), and does not apply if a different time is set by a statute, local rule, or order in the case. A local rule may, for example, address the problems that might arise if a single district has clerk’s offices in different time zones, or provide that papers filed in a drop box after the normal hours of the clerk’s office are filed as of the day that is date-stamped on the papers by a device in the drop box.

28 U.S.C. §452 provides that “[a]ll courts of the United States shall be deemed always open for the purpose of filing proper papers, issuing and returning process, and making motions and orders.” A corresponding provision exists in Rule 77(a). Some courts have held that these provisions permit an after-hours filing by handing the papers to an appropriate official. See, e.g., Casalduc v. Diaz, 117 F.2d 915, 917 (1st Cir. 1941). Subdivision (a)(4) does not address the effect of the statute on the question of after-hours filing; instead, the rule is designed to deal with filings in the ordinary course without regard to Section 452.

Subdivision (a)(5). New subdivision (a)(5) defines the “next” day for purposes of subdivisions (a)(1)(C) and (a)(2)(C). The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure contain both forward-looking time periods and backward-looking time periods. A forward-looking time period requires something to be done within a period of time after an event. See, e.g., Rule 59(b) (motion for new trial “must be filed no later than 28 days after entry of the judgment”). A backward-looking time period requires something to be done within a period of time beforean event. See, e.g., Rule 26(f) (parties must hold Rule 26(f) conference “as soon as practicable and in any event at least 21 days before a scheduling conference is held or a scheduling order is due under Rule 16(b)”). In determining what is the “next” day for purposes of subdivisions (a)(1)(C) and (a)(2)(C), one should continue counting in the same direction—that is, forward when computing a forward-looking period and backward when computing a backward-looking period. If, for example, a filing is due within 30 days after an event, and the thirtieth day falls on Saturday, September 1, 2007, then the filing is due on Tuesday, September 4, 2007 (Monday, September 3, is Labor Day). But if a filing is due 21 days before an event, and the twenty-first day falls on Saturday, September 1, then the filing is due on Friday, August 31. If the clerk’s office is inaccessible on August 31, then subdivision (a)(3) extends the filing deadline forward to the next accessible day that is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday—no later than Tuesday, September 4.

Subdivision (a)(6). New subdivision (a)(6) defines “legal holiday” for purposes of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, including the time-computation provisions of subdivision (a). Subdivision (a)(6) continues to include within the definition of “legal holiday” days that are declared a holiday by the President or Congress.

For forward-counted periods— i.e., periods that are measured after an event—subdivision (a)(6)(C) includes certain state holidays within the definition of legal holidays. However, state legal holidays are not recognized in computing backward-counted periods. For both forward- and backward-counted periods, the rule thus protects those who may be unsure of the effect of state holidays. For forward-counted deadlines, treating state holidays the same as federal holidays extends the deadline. Thus, someone who thought that the federal courts might be closed on a state holiday would be safeguarded against an inadvertent late filing. In contrast, for backward-counted deadlines, not giving state holidays the treatment of federal holidays allows filing on the state holiday itself rather than the day before. Take, for example, Monday, April 21, 2008 (Patriot’s Day, a legal holiday in the relevant state). If a filing is due 14 days after an event, and the fourteenth day is April 21, then the filing is due on Tuesday, April 22 because Monday, April 21 counts as a legal holiday. But if a filing is due 14 days before an event, and the fourteenth day is April 21, the filing is due on Monday, April 21; the fact that April 21 is a state holiday does not make April 21 a legal holiday for purposes of computing this backward-counted deadline. But note that if the clerk’s office is inaccessible on Monday, April 21, then subdivision (a)(3) extends the April 21 filing deadline forward to the next accessible day that is not a Saturday, Sunday or legal holiday—no earlier than Tuesday, April 22.

Changes Made after Publication and Comment. The Standing Committee changed Rule 6(a)(6) to exclude state holidays from the definition of “legal holiday” for purposes of computing backward-counted periods; conforming changes were made to the Committee Note.

[ Subdivisions (b) and (c). ] The times set in the former rule at 1 or 5 days have been revised to 7 or 14 days. See the Note to Rule 6 [above].

Committee Notes on Rules—2016 Amendment

Rule 6(d) is amended to remove service by electronic means under Rule 5(b)(2)(E) from the modes of service that allow 3 added days to act after being served.

Rule 5(b)(2) was amended in 2001 to provide for service by electronic means. Although electronic transmission seemed virtually instantaneous even then, electronic service was included in the modes of service that allow 3 added days to act after being served. There were concerns that the transmission might be delayed for some time, and particular concerns that incompatible systems might make it difficult or impossible to open attachments. Those concerns have been substantially alleviated by advances in technology and in widespread skill in using electronic transmission.

A parallel reason for allowing the 3 added days was that electronic service was authorized only with the consent of the person to be served. Concerns about the reliability of electronic transmission might have led to refusals of consent; the 3 added days were calculated to alleviate these concerns.

Diminution of the concerns that prompted the decision to allow the 3 added days for electronic transmission is not the only reason for discarding this indulgence. Many rules have been changed to ease the task of computing time by adopting 7- , 14 -, 21 -, and 28- day periods that allow “day – of-the -week” counting. Adding 3 days at the end complicated the counting, and increased the occasions for further complication by invoking the provisions that apply when the last day is a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday.

Electronic service after business hours, or just before or during a weekend or holiday, may result in a practical reduction in the time available to respond. Extensions of time may be warranted to prevent prejudice.

Eliminating Rule 5(b) subparagraph (2)(E) from the modes of service that allow 3 added days means that the 3 added days cannot be retained by consenting to service by electronic means. Consent to electronic service in registering for electronic case filing, for example, does not count as consent to service “by any other means” of delivery under subparagraph (F).

What is now Rule 6(d) was amended in 2005 “to remove any doubt as to the method for calculating the time to respond after service by mail, leaving with the clerk of court, electronic means, or by other means consented to by the party served.” A potential ambiguity was created by substituting “after service” for the earlier ref erences to acting after service “upon the party” if a paper or notice “is served upon the party” by the specified means. “[A]fter service” could be read to refer not only to a party that has been served but also to a party that has made service. That reading would mean that a party who is allowed a specified time to act after making service can extend the time by choosing one of the means of service specified in the rule, something that was never intended by the original rule or the amendment. Rules sett ing a time to act after making service include Rules 14(a)(1), 15(a)(1)(A), and 38(b)(1). “[A]fter being served” is substituted for “after service” to dispel any possible misreading.

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure – Rule 26. Computing and Extending Time

(a) Computing Time. The following rules apply in computing any time period specified in these rules, in any local rule or court order, or in any statute that does not specify a method of computing time.

(1) Period Stated in Days or a Longer Unit. When the period is stated in days or a longer unit of time:

(A) exclude the day of the event that triggers the period;

(B) count every day, including intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays; and

(C) include the last day of the period, but if the last day is a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday, the period continues to run until the end of the next day that is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday.

(2) Period Stated in Hours. When the period is stated in hours:

(A) begin counting immediately on the occurrence of the event that triggers the period;

(B) count every hour, including hours during intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays; and

(C) if the period would end on a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday, the period continues to run until the same time on the next day that is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday.

(3) Inaccessibility of the Clerk’s Office. Unless the court orders otherwise, if the clerk’s office is inaccessible:

(A) on the last day for filing under Rule 26(a)(1), then the time for filing is extended to the first accessible day that is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday; or

(B) during the last hour for filing under Rule 26(a)(2), then the time for filing is extended to the same time on the first accessible day that is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday.

(4) “Last Day” Defined. Unless a different time is set by a statute, local rule, or court order, the last day ends:

(A) for electronic filing in the district court, at midnight in the court’s time zone;

(B) for electronic filing in the court of appeals, at midnight in the time zone of the circuit clerk’s principal office;

(C) for filing under Rules 4(c)(1), 25(a)(2)(B), and 25(a)(2)(C)—and filing by mail under Rule 13(a)(2)—at the latest time for the method chosen for delivery to the post office, third-party commercial carrier, or prison mailing system; and

(D) for filing by other means, when the clerk’s office is scheduled to close.

(5) “Next Day” Defined. The “next day” is determined by continuing to count forward when the period is measured after an event and backward when measured before an event.

(6) “Legal Holiday” Defined. “Legal holiday” means:

(A) the day set aside by statute for observing New Year’s Day, Martin Luther King Jr.’s Birthday, Washington’s Birthday, Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Columbus Day, Veterans’ Day, Thanksgiving Day, or Christmas Day;

(B) any day declared a holiday by the President or Congress; and

(C) for periods that are measured after an event, any other day declared a holiday by the state where either of the following is located: the district court that rendered the challenged judgment or order, or the circuit clerk’s principal office.

(b) Extending Time. For good cause, the court may extend the time prescribed by these rules or by its order to perform any act, or may permit an act to be done after that time expires. But the court may not extend the time to file:

(1) a notice of appeal (except as authorized in Rule 4) or a petition for permission to appeal; or

(2) a notice of appeal from or a petition to enjoin, set aside, suspend, modify, enforce, or otherwise review an order of an administrative agency, board, commission, or officer of the United States, unless specifically authorized by law.

(c) Additional Time after Certain Kinds of Service. When a party may or must act within a specified time after being served, 3 days are added after the period would otherwise expire under Rule 26(a), unless the paper is delivered on the date of service stated in the proof of service. For purposes of this Rule 26(c), a paper that is served electronically is treated as delivered on the date of service stated in the proof of service.

Notes

(As amended Mar. 1, 1971, eff. July 1, 1971; Mar. 10, 1986, eff. July 1, 1986; Apr. 25, 1989, eff. Dec. 1, 1989; Apr. 30, 1991, eff. Dec. 1, 1991; Apr. 23, 1996, eff. Dec. 1, 1996; Apr. 24, 1998, eff. Dec. 1, 1998; Apr. 29, 2002, eff. Dec. 1, 2002; Apr. 25, 2005, eff. Dec. 1, 2005; Mar. 26, 2009, eff. Dec. 1, 2009; Apr. 28, 2016, eff. Dec 1, 2016.)

Notes of Advisory Committee on Rules—1967

The provisions of this rule are based upon FRCP 6 (a), (b) and (e). See also Supreme Court Rule 34 and FRCrP 45. Unlike FRCP 6 (b), this rule, read with Rule 27, requires that every request for enlargement of time be made by motion, with proof of service on all parties. This is the simplest, most convenient way of keeping all parties advised of developments. By the terms of Rule 27(b) a motion for enlargement of time under Rule 26(b) may be entertained and acted upon immediately, subject to the right of any party to seek reconsideration. Thus the requirement of motion and notice will not delay the granting of relief of a kind which a court is inclined to grant as of course. Specifically, if a court is of the view that an extension of time sought before expiration of the period originally prescribed or as extended by a previous order ought to be granted in effect ex parte, as FRCP 6(b) permits, it may grant motions seeking such relief without delay.

Notes of Advisory Committee on Rules—1971 Amendment

The amendment adds Columbus Day to the list of legal holidays to conform the subdivision to the Act of June 28, 1968, 82 Stat. 250, which constituted Columbus Day a legal holiday effective after January 1, 1971.

The Act, which amended Title 5, U.S.C. §6103(a), changes the day on which certain holidays are to be observed. Washington’s Birthday, Memorial Day and Veterans Day are to be observed on the third Monday in February, the last Monday in May and the fourth Monday in October, respectively, rather than, as heretofore, on February 22, May 30, and November 11, respectively. Columbus Day is to be observed on the second Monday in October. New Year’s Day, Independence Day, Thanksgiving Day and Christmas continue to be observed on the traditional days.

Notes of Advisory Committee on Rules—1986 Amendment

The Birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr., is added to the list of national holidays in Rule 26(a). The amendment to Rule 26(c) is technical. No substantive change is intended.

Notes of Advisory Committee on Rules—1989 Amendment

The proposed amendment brings Rule 26(a) into conformity with the provisions of Rule 6(a) of the Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 45(a) of the Rules of Criminal Procedure, and Rule 9006(a) of the Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure which allow additional time for filing whenever a clerk’s office is inaccessible on the last day for filing due to weather or other conditions.

Notes of Advisory Committee on Rules—1996 Amendment

The amendment is a companion to the proposed amendments to Rule 25 that permit service on a party by commercial carrier. The amendments to subdivision (c) of this rule make the three-day extension applicable not only when service is accomplished by mail, but whenever delivery to the party being served occurs later than the date of service stated in the proof of service. When service is by mail or commercial carrier, the proof of service recites the date of mailing or delivery to the commercial carrier. If the party being served receives the paper on a later date, the three-day extension applies. If the party being served receives the paper on the same date as the date of service recited in the proof of service, the three-day extension is not available.

The amendment also states that the three-day extension is three calendar days. Rule 26(a) states that when a period prescribed or allowed by the rules is less than seven days, intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays do not count. Whether the three-day extension in Rule 26(c) is such a period, meaning that three-days could actually be five or even six days, is unclear. The D.C. Circuit recently held that the parallel three-day extension provided in the Civil Rules is not such a period and that weekends and legal holidays do count. CNPq v. Inter-Trade, 50 F.3d 56 (D.C. Cir. 1995). The Committee believes that is the right result and that the issue should be resolved. Providing that the extension is three calendar days means that if a period would otherwise end on Thursday but the three-day extension applies, the paper must be filed on Monday. Friday, Saturday, and Sunday are the extension days. Because the last day of the period as extended is Sunday, the paper must be filed the next day, Monday.

Committee Notes on Rules—1998 Amendment

The language and organization of the rule are amended to make the rule more easily understood. In addition to changes made to improve the understanding, the Advisory Committee has changed language to make style and terminology consistent throughout the appellate rules. These changes are intended to be stylistic only; two substantive changes are made, however, in subdivision (a).

Subdivision (a). First, the amendments make the computation method prescribed in this rule applicable to any time period imposed by a local rule. This means that if a local rule establishing a time limit is permitted, the national rule will govern the computation of that period.

Second, paragraph (a)(2) includes language clarifying that whenever the rules establish a time period in “calendar days,” weekends and legal holidays are counted.

Committee Notes on Rules—2002 Amendment

Subdivision (a)(2). The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure compute time differently than the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure. Fed. R. Civ. P. 6 (a) and Fed. R. Crim. P. 45 (a) provide that, in computing any period of time, “[w]hen the period of time prescribed or allowed is less than 11 days, intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays shall be excluded in the computation.” By contrast, Rule 26(a)(2) provides that, in computing any period of time, a litigant should “[e]xclude intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays when the period is less than 7 days, unless stated in calendar days.” Thus, deadlines of 7, 8, 9, and 10 days are calculated differently under the rules of civil and criminal procedure than they are under the rules of appellate procedure. This creates a trap for unwary litigants. No good reason for this discrepancy is apparent, and thus Rule 26(a)(2) has been amended so that, under all three sets of rules, intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays will be excluded when computing deadlines under 11 days but will be counted when computing deadlines of 11 days and over.

Changes Made After Publication and Comments. No changes were made to the text of the proposed amendment or to the Committee Note.

Subdivision (c). Rule 26(c) has been amended to provide that when a paper is served on a party by electronic means, and that party is required or permitted to respond to that paper within a prescribed period, 3 calendar days are added to the prescribed period. Electronic service is usually instantaneous, but sometimes it is not, because of technical problems. Also, if a paper is electronically transmitted to a party on a Friday evening, the party may not realize that he or she has been served until two or three days later. Finally, extending the “3-day rule” to electronic service will encourage parties to consent to such service under Rule 25(c).

Changes Made After Publication and Comments. No changes were made to the text of the proposed amendment or to the Committee Note.

Committee Notes on Rules—2005 Amendment

Subdivision (a)(4). Rule 26(a)(4) has been amended to refer to the third Monday in February as “Washington’s Birthday.” A federal statute officially designates the holiday as “Washington’s Birthday,” reflecting the desire of Congress specially to honor the first president of the United States. See 5 U.S.C. §6103(a). During the 1998 restyling of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, references to “Washington’s Birthday” were mistakenly changed to “Presidents’ Day.” The amendment corrects that error.

Changes Made After Publication and Comments. No changes were made to the text of the proposed amendment or to the Committee Note.

Committee Notes on Rules—2009 Amendment

Subdivision (a). Subdivision (a) has been amended to simplify and clarify the provisions that describe how deadlines are computed. Subdivision (a) governs the computation of any time period found in a statute that does not specify a method of computing time, a Federal Rule of Appellate Procedure, a local rule, or a court order. In accordance with Rule 47(a)(1), a local rule may not direct that a deadline be computed in a manner inconsistent with subdivision (a).

The time-computation provisions of subdivision (a) apply only when a time period must be computed. They do not apply when a fixed time to act is set. The amendments thus carry forward the approach taken in Violette v. P.A. Days, Inc., 427 F.3d 1015, 1016 (6th Cir. 2005) (holding that Civil Rule 6(a) “does not apply to situations where the court has established a specific calendar day as a deadline”), and reject the contrary holding of In re American Healthcare Management, Inc., 900 F.2d 827, 832 (5th Cir. 1990) (holding that Bankruptcy Rule 9006(a) governs treatment of date-certain deadline set by court order). If, for example, the date for filing is “no later than November 1, 2007,” subdivision (a) does not govern. But if a filing is required to be made “within 10 days” or “within 72 hours,” subdivision (a) describes how that deadline is computed.

Subdivision (a) does not apply when computing a time period set by a statute if the statute specifies a method of computing time. See, e.g., 20 U.S.C. §7711(b)(1) (requiring certain petitions for review by a local educational agency or a state to be filed “within 30 working days (as determined by the local educational agency or State) after receiving notice of” federal agency decision).

Subdivision (a)(1). New subdivision (a)(1) addresses the computation of time periods that are stated in days. It also applies to time periods that are stated in weeks, months, or years; though no such time period currently appears in the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, such periods may be set by other covered provisions such as a local rule. See, e.g., Third Circuit Local Appellate Rule 46.3(c)(1). Subdivision (a)(1)(B)’s directive to “count every day” is relevant only if the period is stated in days (not weeks, months or years).

Under former Rule 26(a), a period of 11 days or more was computed differently than a period of less than 11 days. Intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays were included in computing the longer periods, but excluded in computing the shorter periods. Former Rule 26(a) thus made computing deadlines unnecessarily complicated and led to counterintuitive results. For example, a 10-day period and a 14-day period that started on the same day usually ended on the same day—and the 10-day period not infrequently ended later than the 14-day period. See Miltimore Sales, Inc. v. Int’l Rectifier, Inc., 412 F.3d 685, 686 (6th Cir. 2005).

Under new subdivision (a)(1), all deadlines stated in days (no matter the length) are computed in the same way. The day of the event that triggers the deadline is not counted. All other days—including intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays—are counted, with only one exception: If the period ends on a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday, then the deadline falls on the next day that is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday. An illustration is provided below in the discussion of subdivision (a)(5). Subdivision (a)(3) addresses filing deadlines that expire on a day when the clerk’s office is inaccessible.

Where subdivision (a) formerly referred to the “act, event, or default” that triggers the deadline, new subdivision (a) refers simply to the “event” that triggers the deadline; this change in terminology is adopted for brevity and simplicity, and is not intended to change meaning.

Periods previously expressed as less than 11 days will be shortened as a practical matter by the decision to count intermediate Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays in computing all periods. Many of those periods have been lengthened to compensate for the change. See, e.g., Rules 5(b)(2), 5(d)(1), 28.1(f), & 31(a).

Most of the 10-day periods were adjusted to meet the change in computation method by setting 14 days as the new period. A 14-day period corresponds to the most frequent result of a 10-day period under the former computation method—two Saturdays and two Sundays were excluded, giving 14 days in all. A 14-day period has an additional advantage. The final day falls on the same day of the week as the event that triggered the period—the 14th day after a Monday, for example, is a Monday. This advantage of using week-long periods led to adopting 7-day periods to replace some of the periods set at less than 10 days, and 21-day periods to replace 20-day periods. Thirty-day and longer periods, however, were retained without change.

Subdivision (a)(2). New subdivision (a)(2) addresses the computation of time periods that are stated in hours. No such deadline currently appears in the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure. But some statutes contain deadlines stated in hours, as do some court orders issued in expedited proceedings.

Under subdivision (a)(2), a deadline stated in hours starts to run immediately on the occurrence of the event that triggers the deadline. The deadline generally ends when the time expires. If, however, the time period expires at a specific time (say, 2:17 p.m.) on a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday, then the deadline is extended to the same time (2:17 p.m.) on the next day that is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday. Periods stated in hours are not to be “rounded up” to the next whole hour. Subdivision (a)(3) addresses situations when the clerk’s office is inaccessible during the last hour before a filing deadline expires.

Subdivision (a)(2)(B) directs that every hour be counted. Thus, for example, a 72-hour period that commences at 10:00 a.m. on Friday, November 2, 2007, will run until 9:00 a.m. on Monday, November 5; the discrepancy in start and end times in this example results from the intervening shift from daylight saving time to standard time.

Subdivision (a)(3). When determining the last day of a filing period stated in days or a longer unit of time, a day on which the clerk’s office is not accessible because of the weather or another reason is treated like a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday. When determining the end of a filing period stated in hours, if the clerk’s office is inaccessible during the last hour of the filing period computed under subdivision (a)(2) then the period is extended to the same time on the next day that is not a weekend, holiday or day when the clerk’s office is inaccessible.

Subdivision (a)(3)’s extensions apply “[u]nless the court orders otherwise.” In some circumstances, the court might not wish a period of inaccessibility to trigger a full 24-hour extension; in those instances, the court can specify a briefer extension.

The text of the rule no longer refers to “weather or other conditions” as the reason for the inaccessibility of the clerk’s office. The reference to “weather” was deleted from the text to underscore that inaccessibility can occur for reasons unrelated to weather, such as an outage of the electronic filing system. Weather can still be a reason for inaccessibility of the clerk’s office. The rule does not attempt to define inaccessibility. Rather, the concept will continue to develop through caselaw, see, e.g., Tchakmakjian v. Department of Defense, 57 Fed. Appx. 438, 441 (Fed. Cir. 2003) (unpublished per curiam opinion) (inaccessibility “due to anthrax concerns”); cf. William G. Phelps, When Is Office of Clerk of Court Inaccessible Due to Weather or Other Conditions for Purpose of Computing Time Period for Filing Papers under Rule 6(a) of Federal Rules of Civil Procedure , 135 A.L.R. Fed. 259 (1996) (collecting cases). In addition, local provisions may address inaccessibility for purposes of electronic filing.

Subdivision (a)(4). New subdivision (a)(4) defines the end of the last day of a period for purposes of subdivision (a)(1). Subdivision (a)(4) does not apply in computing periods stated in hours under subdivision (a)(2), and does not apply if a different time is set by a statute, local rule, or order in the case. A local rule may, for example, address the problems that might arise under subdivision (a)(4)(A) if a single district has clerk’s offices in different time zones, or provide that papers filed in a drop box after the normal hours of the clerk’s office are filed as of the day that is date-stamped on the papers by a device in the drop box.

28 U.S.C. §452 provides that “[a]ll courts of the United States shall be deemed always open for the purpose of filing proper papers, issuing and returning process, and making motions and orders.” A corresponding provision exists in Rule 45(a)(2). Some courts have held that these provisions permit an after-hours filing by handing the papers to an appropriate official. See, e.g., Casalduc v. Diaz, 117 F.2d 915, 917 (1st Cir. 1941). Subdivision (a)(4) does not address the effect of the statute on the question of after-hours filing; instead, the rule is designed to deal with filings in the ordinary course without regard to Section 452.

Subdivision (a)(4)(A) addresses electronic filings in the district court. For example, subdivision (a)(4)(A) would apply to an electronically-filed notice of appeal. Subdivision (a)(4)(B) addresses electronic filings in the court of appeals.

Subdivision (a)(4)(C) addresses filings by mail under Rules 25(a)(2)(B)(i) and 13(b), filings by third-party commercial carrier under Rule 25(a)(2)(B)(ii), and inmate filings under Rules 4(c)(1) and 25(a)(2)(C). For such filings, subdivision (a)(4)(C) provides that the “last day” ends at the latest time (prior to midnight in the filer’s time zone) that the filer can properly submit the filing to the post office, third-party commercial carrier, or prison mail system (as applicable) using the filer’s chosen method of submission. For example, if a correctional institution’s legal mail system’s rules of operation provide that items may only be placed in the mail system between 9:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m., then the “last day” for filings under Rules 4(c)(1) and 25(a)(2)(C) by inmates in that institution ends at 5:00 p.m. As another example, if a filer uses a drop box maintained by a third-party commercial carrier, the “last day” ends at the time of that drop box’s last scheduled pickup. Filings by mail under Rule 13(b) continue to be subject to §7502 of the Internal Revenue Code, as amended, and the applicable regulations.

Subdivision (a)(4)(D) addresses all other non-electronic filings; for such filings, the last day ends under (a)(4)(D) when the clerk’s office in which the filing is made is scheduled to close.

Subdivision (a)(5). New subdivision (a)(5) defines the “next” day for purposes of subdivisions (a)(1)(C) and (a)(2)(C). The Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure contain both forward-looking time periods and backward-looking time periods. A forward-looking time period requires something to be done within a period of time after an event. See, e.g., Rule 4(a)(1)(A) (subject to certain exceptions, notice of appeal in a civil case must be filed “within 30 days after the judgment or order appealed from is entered”). A backward-looking time period requires something to be done within a period of time before an event. See, e.g., Rule 31(a)(1) (“[A] reply brief must be filed at least 7 days before argument, unless the court, for good cause, allows a later filing.”). In determining what is the “next” day for purposes of subdivisions (a)(1)(C) and (a)(2)(C), one should continue counting in the same direction—that is, forward when computing a forward-looking period and backward when computing a backward-looking period. If, for example, a filing is due within 10 days after an event, and the tenth day falls on Saturday, September 1, 2007, then the filing is due on Tuesday, September 4, 2007 (Monday, September 3, is Labor Day). But if a filing is due 10 days before an event, and the tenth day falls on Saturday, September 1, then the filing is due on Friday, August 31. If the clerk’s office is inaccessible on August 31, then subdivision (a)(3) extends the filing deadline forward to the next accessible day that is not a Saturday, Sunday or legal holiday—no earlier than Tuesday, September 4.

Subdivision (a)(6). New subdivision (a)(6) defines “legal holiday” for purposes of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, including the time-computation provisions of subdivision (a). Subdivision (a)(6) continues to include within the definition of “legal holiday” days that are declared a holiday by the President or Congress.

For forward-counted periods—i.e., periods that are measured after an event—subdivision (a)(6)(C) includes certain state holidays within the definition of legal holidays. However, state legal holidays are not recognized in computing backward-counted periods. For both forward- and backward-counted periods, the rule thus protects those who may be unsure of the effect of state holidays. For forward-counted deadlines, treating state holidays the same as federal holidays extends the deadline. Thus, someone who thought that the federal courts might be closed on a state holiday would be safeguarded against an inadvertent late filing. In contrast, for backward-counted deadlines, not giving state holidays the treatment of federal holidays allows filing on the state holiday itself rather than the day before. Take, for example, Monday, April 21, 2008 (Patriot’s Day, a legal holiday in the relevant state). If a filing is due 14 days after an event, and the fourteenth day is April 21, then the filing is due on Tuesday, April 22 because Monday, April 21 counts as a legal holiday. But if a filing is due 14 days before an event, and the fourteenth day is April 21, the filing is due on Monday, April 21; the fact that April 21 is a state holiday does not make April 21 a legal holiday for purposes of computing this backward-counted deadline. But note that if the clerk’s office is inaccessible on Monday, April 21, then subdivision (a)(3) extends the April 21 filing deadline forward to the next accessible day that is not a Saturday, Sunday or legal holiday—no earlier than Tuesday, April 22.

Subdivision (c). To specify that a period should be calculated by counting all intermediate days, including weekends or holidays, the Rules formerly used the term “calendar days.” Because new subdivision (a) takes a “days-are-days” approach under which all intermediate days are counted, no matter how short the period, “3 calendar days” in subdivision (c) is amended to read simply “3 days.”

Rule 26(c) has been amended to eliminate uncertainty about application of the 3-day rule. Civil Rule 6(e) was amended in 2004 to eliminate similar uncertainty in the Civil Rules.

Under the amendment, a party that is required or permitted to act within a prescribed period should first calculate that period, without reference to the 3-day rule provided by Rule 26(c), but with reference to the other time computation provisions of the Appellate Rules. After the party has identified the date on which the prescribed period would expire but for the operation of Rule 26(c), the party should add 3 calendar days. The party must act by the third day of the extension, unless that day is a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday, in which case the party must act by the next day that is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday.

To illustrate: A paper is served by mail on Thursday, November 1, 2007. The prescribed time to respond is 30 days. The prescribed period ends on Monday, December 3 (because the 30th day falls on a Saturday, the prescribed period extends to the following Monday). Under Rule 26(c), three calendar days are added—Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday—and thus the response is due on Thursday, December 6.

Changes Made After Publication and Comment. No changes were made after publication and comment, except for the style changes (described below) [omitted] which were suggested by Professor Kimble.

Committee Notes on Rules—2016 Amendment

Subdivision (a)(4)(C). The reference to Rule 13(b) is revised to refer to Rule 13(a)(2) in light of a 2013 amendment to Rule 13. The amendment to subdivision (a)(4)(C) is technical and no substantive change is intended.

Subdivision (c). Rule 26(c) is amended to remove service by electronic means under Rule 25(c)(1)(D) from the modes of service that allow 3 added days to act after being served.

Rule 25(c) was amended in 2002 to provide for service by electronic means. Although electronic transmission seemed virtually instantaneous even then, electronic service was included in the modes of service that allow 3 added days to act after being served. There were concerns that the transmission might be delayed for some time, and particular concerns that incompatible systems might make it difficult or impossible to open attachments. Those concerns have been substantially alleviated by advances in technology and widespread skill in using electronic transmission.

A parallel reason for allowing the 3 added days was that electronic service was authorized only with the consent of the person to be served. Concerns about the reliability of electronic transmission might have led to refusals of consent; the 3 added days were calculated to alleviate these concerns.

Diminution of the concerns that prompted the decision to allow the 3 added days for electronic transmission is not the only reason for discarding this indulgence. Many rules have been changed to ease the task of computing time by adopting 7-, 14-, 21-, and 28- day periods that allow “day- of-the-week” counting. Adding 3 days at the end complicated the counting, and increased the occasions for further complication by invoking the provisions that apply when the last day is a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday.

Electronic service after business hours, or just before or during a weekend or holiday, may result in a practical reduction in the time available to respond. Extensions of time may be warranted to prevent prejudice.

Rule 26(c) has also been amended to refer to instances when a party “may or must act . . . after being served” rather than to instances when a party “may or must act . . . after service.” If, in future, an Appellate Rule sets a deadline for a party to act after that party itself effects service on another person, this change in language will clarify that Rule 26(c)’s three added days are not accorded to the party who effected service.

COLORADO REVISED STATUTES

*** Titles 1 through 11, 13 to 17, 19 through 21, 23, 25 through 38, and 40 through 43 of the Colorado Statutes have been updated and are current through all laws passed during the 2016 Legislative Session, subject to final review by the Colorado Office of Legislative Legal Services. The remainder of the titles are current through all laws passed during the 2015 Legislative Session and are in the process of being updated. ***

TITLE 1. ELECTIONS

GENERAL, PRIMARY, RECALL, AND CONGRESSIONAL VACANCY ELECTIONS

ARTICLE 1.ELECTIONS GENERALLY

PART 1. DEFINITIONS AND GENERAL PROVISIONS

C.R.S. 1-1-106 (2016)

1-1-106. Computation of time

(1) Calendar days shall be used in all computations of time made under the provisions of this code.

(2) In computing any period of days prescribed by this code, the day of the act or event from which the designated period of days begins to run shall not be included and the last day shall be included. Saturdays, Sundays, and legal holidays shall be included, except as provided in subsection (4) of this section.

(3) If a number of months is to be computed by counting the months from a particular day, the period shall end on the same numerical day in the concluding month as the day of the month from which the computation is begun; except that, if there are not that many days in the concluding month, the counting period shall end on the last day of the concluding month.

(4) If the last day for any act to be done or the last day of any period is a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday and completion of such act involves a filing or other action during business hours, the period is extended to include the next day which is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday.

(5) If the state constitution or a state statute requires doing an act in “not less than” or “no later than” or “at least” a certain number of days or “prior to” a certain number of days or a certain number of months “before” the date of an election, or any phrase that suggests a similar meaning, the period is shortened to and ends on the prior business day that is not a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday, except as provided in section 1-2-201 (3).

HISTORY: Source: L. 92: Entire article R&RE, p. 631, § 1, effective January 1, 1993.L. 93: (5) amended, p. 1395, § 3, effective July 1.L. 95: (2) and (5) amended, p. 820, § 2, effective July 1.L. 96: (5) amended, p. 1773, § 76, effective July 1.L. 99: (4) and (5) amended, p. 756, § 2, effective May 20.

Editor’s note: This section is similar to former § 1-1-105 as it existed prior to 1992.

Cross references: For computation of time under the statutes generally, see § 2-4-108.

ANNOTATION

This section shall be used in all computations of time made under the provisions of the elections statutes which relate to general, primary, and special (now congressional vacancy) elections. Ray v. Mickelson, 196 Colo. 325, 584 P.2d 1215 (1978) (decided under former law).

Copyright (c) 2016 by Matthew Bender & Company Inc.

All rights reserved

*** This document reflects changes received through February 19, 2016 ***

COLORADO RULES OF CIVIL PROCEDURE

CHAPTER 1 SCOPE OF RULES, ONE FORM OF ACTION, COMMENCEMENT OF ACTION, SERVICE OF PROCESS, PLEADINGS, MOTIONS AND ORDERS

C.R.C.P. 6 (2016)

Rule 6. Time.

(a) Computation.